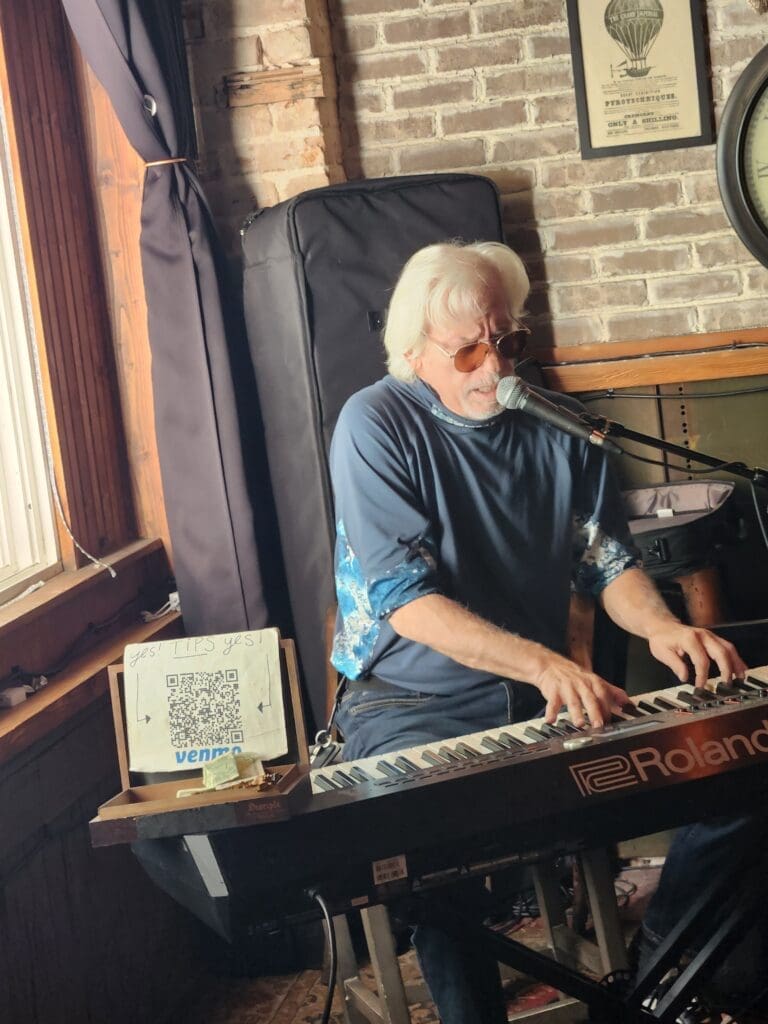

- The first time I caught pianist,Tony Castellano Jr, I was, perched on a stool, sitting around a grand piano. Its keys suddenly seemed to span one hundred and eighty-eight, instead of the piano’s usual eighty-eight. Having a two-week pass to St Pete Yacht club, my husband and I had headed straight for the piano lounge. Across a slate-black beauty, in between renditions from the American Song book, Billy Joel, and some classical turns, Tony, always upbeat and affable, occasionally shared some witty quip. He also tossed out that he was at “The Parrot” on Monday nights. Monday evening found us in a deserted area of Corey Avenue, staring at a wooden building that, at best, was a kind of fish shack. We wondered if this could possibly be The Parrot, doubtful a piano had ever entered in with the fishing nets.

And why were there so many cars in the dusty parking area? A couple of old salts sat at the bar inside. The terse bartender said, “Around the back.” Was this the 1920s? Prohibition? We walked around the weathered clapboards to a yard filled with picnic tables, a small bar, twinkling lights, and serious dancers (everyone in St Pete and environs takes swing lessons). Like reaching the Emerald City, before us were elevated stands aglow in bright lights, holding an eighteen-piece orchestra. Tony Castellano, Jr, was far stage right, at the Keyboard. We’d found Tom Katz, then in its twenty-third year of big-band swing at The Blue Parrot. It’s now at a 30-year record. Since then, we’ve traveled to a busy, posh Italian restaurant, Timpano’s, in Tampa, to a family run Italian Trattoria at a strip mall fifteen miles out of St Pete where we were the only customers that night. Needless to say, the food was cooked to order. We’ve caught him at Ruby’s Thursday evenings, and at the Copper Kettle, doing a duo turn with Gloria West. When we’re feeling a bit tony, pun intended it’s cocktails at Mahaffey’s Sonata. All to see Tony’s ever-changing shock of hair at the piano, playing his rich heart out with every note.

The one place we never miss, Wednesday evening after Wednesday evening, month after month, is the Detroit, at 201 Central. You’ll also find him there Sunday afternoons. But on Wednesday, from 9 to midnight or later, Tony C is pounding out jazz. He might insert a brief solo turn, putting us in a melancholy mood with one of his own, lyrical, or thoughtful compositions, or in pure admiration, not appropriation, channel Satchmo, breaking our hearts with “What A Wonderful World.” His Wednesday night band at The Detroit consists of Kenny Loomer, drummer extraordinaire, Mark Gould, an inventive saxophonist, Tom Parmerter the most powerful Trumpeter around, (the latter two also extraordinary) and talented Joe Saunders, shining in a spattering of rock tunes. Other occasional talented friends of Tony’s from Ruby’s, or his musical incarnations in Miami and Atlanta, might pop up.

I could hear the sometimes wild, sometimes sweet sounds of a piano, a horn, a steady drumbeat, with some guitar thrown in, bouncing off the buildings

Tony had an uneven early childhood. With his mother sick, his maternal grandparents raising him, they decided that Chicago, with its drug scene, wasn’t a place for a boy to grow up. They sent six-year-old Tony to Miami to meet his father. That meeting was less memorable to Tony than when, after a year with his paternal grandparents, he stepped into his dad’s apartment and met his first piano. In a moment one can choose to interpret as fateful, psychic, spiritual, or fantasy, little Tony Castellano, Jr experienced an epiphany. As Tony describes it, everything stopped, and he had a vision. As he stared at that piano, like a cash register tallying numbers, every gig he’d ever play was flashing before him. At seven, he, of course, had no idea what those fleeting images meant. He did know, however, that somehow, that piano was going to be his life.

Tony ‘s training was unique. His jazz pianist father never chose to teach his son his own craft. Nor did his uncle Dolph, who, like Tony’s dad, was also into jazz, as well as classical music. He’s had two formal piano lessons. Sinatra, Tony Bennett, and Peggy Lee were on the the radio, and musical variety shows were on the tv. Tony listened. His dad had band rehearsals in the apartment, and tapes of the band’s performances were played into the early a.m. hours, after a gig. From his bed, little Tony heard it all. At one point, his dad, trying to sleep during the day as many musicians do, angrily told him to shut off the record player, “He’s playing my Scarlatti.” he yelled. Bonnie, his dad’s partner, “Ma” to Tony, called back in surprise, “It’s the kid.” His father came in and saw Tony playing the classical Italian compositions he’d heard his uncle and dad listen to. “His feet don’t even touch the ground!” His father was immediately humbled. Innately, Tony had a very good ear. With his father at gigs at night and sleeping much of the day, and Bonnie working the long day shifts of a nurse, Tony was left on his own. All he had was the piano. Once his younger sister came along, at eight, Tony became her caretaker and thus still relegated to staying in. The piano became all the friends he didn’t get to have. As Tony describes it, the piano was like a magnet, his hands stretched out before him pulled to its force.

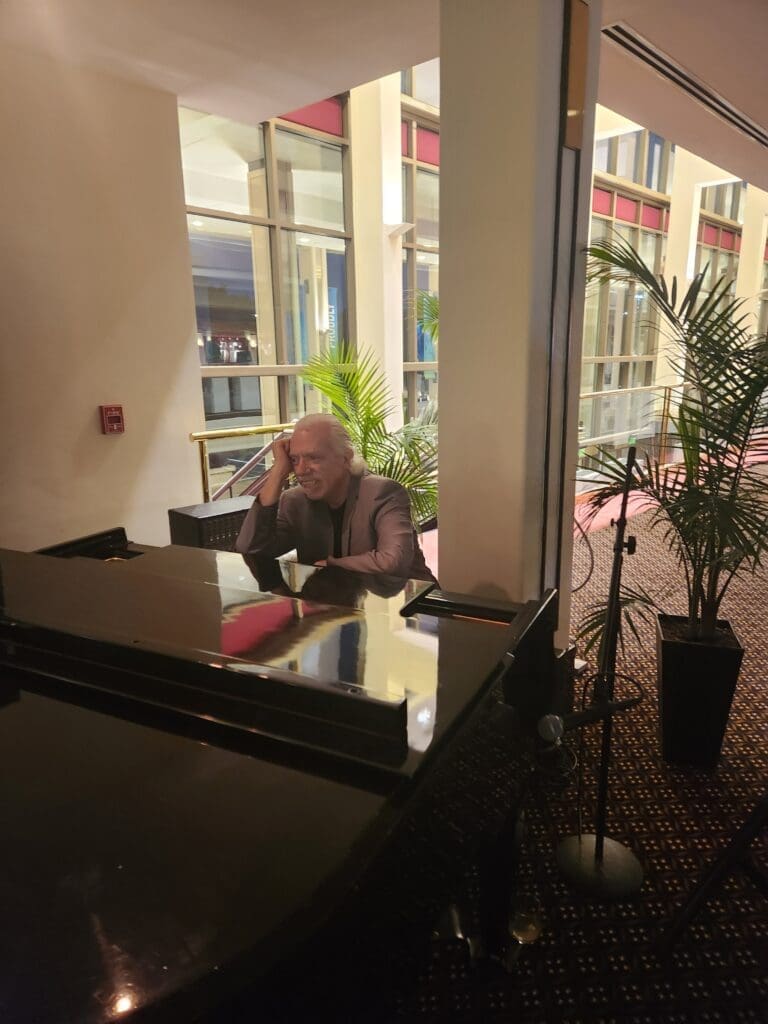

Tony Castellano Jr at piano

His first gig was a bar mitzvah at age 15. By then, the family had moved to Virginia, where an ashram and a well-known guru entered the picture, but that’s a sidebar into his erratic childhood. In Virginia, he put together some fellow musicians. Once, he had to cover for his father at a Holiday Inn. His dad sent him in with no rehearsal, saying, “Just stick to the black keys, they’re all there.” An older bass player befriended him and helped him get gigs.

His first truly big-time, professional gig happened at eighteen, when he opened for Ray Charles at the Brandon Theatre. Nothing like starting at the top. At Virginia Beach, he played with Richie Cole, the alto Sax master and composer, committed to bee-bop.

Tony spread his wings to Atlanta and Miami, in search of more jazz. There had been a brief stab at school, and small departures in other fields. One, through a family connection, got him involved in Florida, helping large companies lower their fuel bills. Any work that didn’t involve music and his piano, however, was short lived. He discovered the Clearwater Jazz festival. It was there he met Kenny Loomer, and not long after, Joe, Saunders. At that festival, he played with esteemed flutist, Herbie Mann. St Pete made sense for Tony because he was centrally located for work in Tampa, Clearwater, Sarasota, Dunedin, etc., all places where Jazz was appreciated. Our gain.

Tony Castellano Jr has described music as love. That’s evident in how open he is to letting other musicians, even those less skilled, sit in for a number or two at least once, sometimes more. His jovial, usually buoyant demeanor covers a tender heart, evident in that openness and in his playing. There isn’t a dishonest creative bone in those long, whizzing fingers of his, or in his clear, nuanced voice, nor in the tunes he has penned. He appears to be an artist devoid of the stereotypical “artistic temperament.” He watched his father complain and turn down work.

Tony, the little boy that knew the piano would be his life and his livelihood is, if anything, undemanding, other than of himself. He learned early on, for financial necessity and longevity, how to be his own bass, playing the bass line with his left hand. Listening to him cascade across the keys, you might think he has four hands.

Tony trusts the universe will carry him along. At age nine, singing with his dad’s band in Miami, an agent from William Morris was interested. His dad declined. The universe was trying, even then, but, ironically, Dad said he didn’t want his son in show business. Tony has played the piano every day since he was seven years old. Dedication and his work ethic has helped the journey. The universe, to Tony, is sound. Everything in him comes from how he hears the world. His ear and heart let him pursue to duplicate, vary, or be inspired to create. I believe sound is his spiritual connection. It has played another profound role in his life. Tony lost his son, Christopher, a few years ago. Christopher’s watch remains in Tony’s possession. Since he’s had it, an alarm, set by his son, goes off each day. Though always thinking of him, at the sound of the buzz, he talks to Christopher, a long-time ritual continued between father and son. Tony claims he went through none of the expected stages of grief. All he feels is sadness, though a month ago, he said he started feeling a little lighter. Missing his son remains, but he feels the grieving period is starting to leave him. By nature, he gives his all in every musical performance. His personal sadness has never showed at the keyboard, unless, perhaps, if possible, in more poignancy in a ballad. As a performer he says he wants people to feel good. His son’s death has evoked yet more of the conviction that he use his music, as his son would have wanted, to the best and most it can be.

Tony Castellano Jr is, indeed, ubiquitous, like Waldo, popping up in surprising places, from private gigs to public arenas, to student’s parlors. He’s played in St Thomas with Bobby Hutchinson, the well-known vibe player; with greats, guitarist Joe D’orio, and sax man Ira Sullivan. He believes his musical life is moving as it should. He is in demand in the Tampa Bay area. His Detroit band regulars, also including popular bassist Hiram Hazley, has been invited to the Clearwater Jazz festival. He has recorded his own clever, or achingly beautiful compositions. One sounds like a string chamber ensemble. A solo, he hit the keys to match the sound he heard in his head. To fulfill his commitment to his son, he is in the process of getting all his compositions out into the recording world. The universe just happened to bring a new music arranger and producer into his life. Maybe it will bring that small jazz club he has always wanted to own or run.

At the pandemics end, I carefully timed my return flight to St Pete. I wanted to be in town by Wednesday eve, of course, to catch Tony Castellano Jr at The Detroit. During the pandemic I was afraid to ask anyone if 201, which some regulars call it, had succumbed to the many pandemic closings. On Second Street South, halfway down the block from number 201 Central, I could hear the sometimes wild, sometimes sweet sounds of a piano, a horn, a steady drumbeat, with some guitar thrown in, bouncing off the buildings. Was it the Janus Arena? Was it some street musician with a pre-recorded background? As I approached The Detroit and stood in the wide window, always open for folks who like to sit at the tables outside, Tony, feet away, looked up and started singing one of his original ballads. I stood in the window and cried. St Pete was still intact.

For me, Tony Castellano Jr is St. Pete. He represents and carries within him all the grit, the hard- earned skill and artistry, endless invention, versatility, creativity, showmanship, and unpredictable funkiness, that make both he and St Pete special.